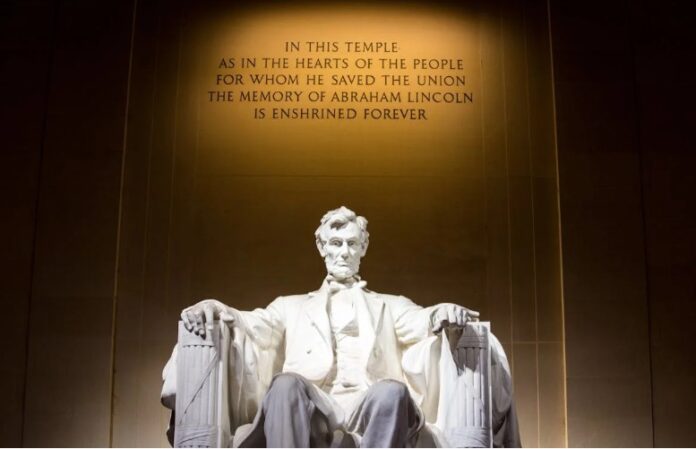

Many aspire to greatness, but for those truly committed to this pursuit, I urge them to look closely at Abraham Lincoln’s face on this President’s Day. As one of the United States’ most pivotal figures, his features resemble a weather-beaten roadmap, etched with the toll of hard physical labor and fault lines of stress. Yet, it’s his eyes that arrest attention. They hold a depth shaped by immense personal tragedy—the loss of three sons—and the crushing weight of safeguarding democracy in the Western Hemisphere. Despite his hardships, his posture—with squared shoulders and an unyielding neck—suggests he was built to carry such a burden. Lincoln’s image serves as a reminder that the cost of greatness is often self-sacrifice, a price so steep that few can afford it.

As a history teacher, I’ve often presented Lincoln as a strangely polarizing figure, both revered and reviled across political divides. However, why is a man who passed the 13th Amendment and led the nation through its most brutal civil war so divisive? I believe this stems, in part, from a lack of historical understanding about who he was and what he believed. In this piece, I aim to address two major misconceptions about Lincoln’s stance on slavery, offering a clearer view of his true legacy.

Claim #1: Lincoln Was a Moderate on Slavery

Lincoln’s political landscape was marked by sharp divisions: abolitionists who called for the complete abolition of slavery and pro-slavery advocates determined to preserve it. While high-profile abolitionists like John Brown, Frederick Douglass, and the Grimké sisters used religious arguments about the image of God in all people, these calls were often dismissed as fanaticism. On the more secular side, figures like William Lloyd Garrison and Victoria Woodhull advocated for broad radical changes and used fiery verbiage, which alienated moderates.

For many Northerners, slavery was a moral dilemma that occupied a backroom in their mind. Politically, they opposed the institution, but as long as slavery was not present in their own states, they felt they could remain content. However, this sense of distance changed after the passage of laws like the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. This law required Northerners to return escaped slaves to their enslavers or face fines and imprisonment. It forced them into direct complicity with the system of slavery, challenging their passive stance of being anti-slavery but not actively involved in its abolition.

Yet, even in their opposition to slavery, the extremism of some abolitionists made it hard for moderates to get involved. Lincoln, however, positioned himself as a moderate, opposing slavery’s expansion without fully embracing radical abolitionist rhetoric. His pragmatic approach allowed him to appeal to a broad audience, including those who feared the extremism of the abolitionist movement.

But was Lincoln truly a moderate? His Republican primary opponent, William Seward, was a known abolitionist, yet it was Lincoln who won the nomination. That said, Southern slave owners feared him so much that they took his name off the ballot and even threatened secession if he won the national election. Lincoln was not a moderate on slavery; he was a leader committed to opposing slavery while navigating the deeply divided nation. His weapon? Knife-sharp precision in his words.

Claim #2: Lincoln Passed the 13th Amendment to Win the War

A popular but flawed belief is that Lincoln passed the 13th Amendment to rally morale during the Civil War. Critics cite a letter Lincoln wrote to Horace Greeley in 1862, in which he stated, “If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it.” Taken out of context, this quote is often used to claim that Lincoln was not truly committed to ending slavery.

However, this interpretation overlooks the wisdom Lincoln displayed in his political maneuvering. In his early years, Lincoln’s focus was on preventing the expansion of slavery, but his views evolved. By the time he issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, Lincoln had made clear his commitment to ending the institution. The 13th Amendment was the next logical step, ensuring the permanent abolition of slavery in the United States.

The Myth of Lincoln’s Racial Moderacy

In the book Lies My Teacher Told Me, James Loewen devotes several chapters to how myths about Lincoln’s racial moderacy were spread by “bad actors” committed to the Lost Cause narrative. These distortions were part of a broader movement in the American South that sought to justify the Confederacy’s actions and preserve a version of history that portrayed slavery as a benign institution and portrayed Lincoln as an imperfect, racially indifferent figure. This far-right narrative has persisted through textbooks and historical accounts written by those sympathetic to the South’s cause or by those simply misled due to generations of bad history.

In the modern era, some on the political left have used these myths to justify tearing down Lincoln’s statues, arguing that his views on race were inconsistent or insufficiently radical. These critics frame Lincoln as a “compromiser” who didn’t do enough for racial justice. While Lincoln’s views on race were undoubtedly shaped by the era in which he lived, his actions speak far more broadly, and when the time was right his public rhetoric evolved to match the moral clarity of his actions.

In his Second Inaugural Address, Lincoln, no longer concerned with re-election, made his views on black equality and racial justice more explicit. He stated, “Yet if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword as was said three thousand years ago so still it must be said ‘the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.”

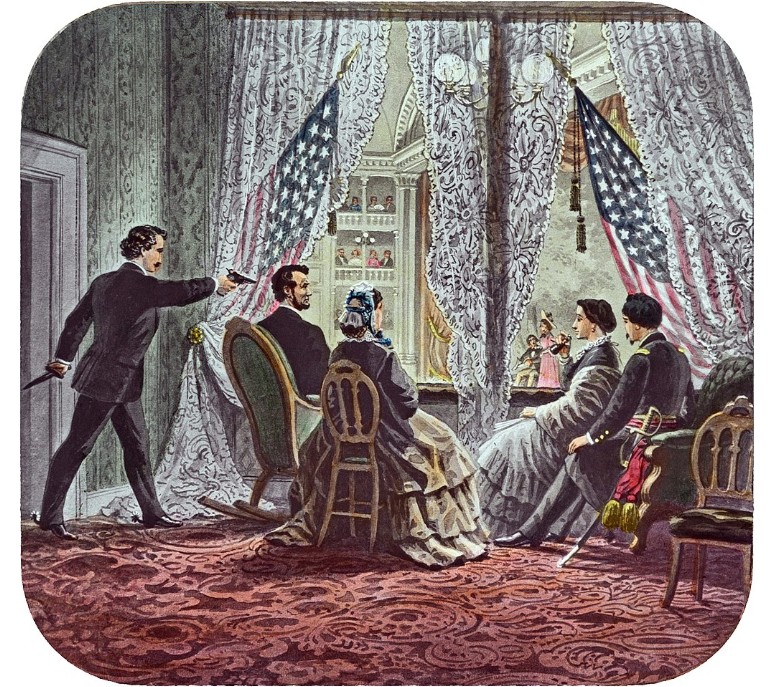

This was a deeply radical stance for the time, one that foreshadowed the profound moral reckoning America was about to face. It also contributed to his assassination, with John Wilkes Booth in the audience, enraged by Lincoln’s words.

A Path Forward: Lincoln’s Wisdom for Today

In our polarized 21st-century America, Lincoln’s words from his second inaugural address offer a way forward: “With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in to bind up the nation’s wounds.” His call to act with “malice toward none” and “charity for all” encourages us to approach each other with empathy, even amid deep disagreements. Lincoln’s emphasis on “firmness in the right” reminds us to stay true to our moral compass, but to do so in a way that fosters reconciliation rather than division.

Ultimately, Lincoln’s vision of a “just and lasting peace” challenges us to rise above partisanship, extend kindness to those with differing views, and work toward common goals. Just as Lincoln did after the Civil War, we too can move forward, united in our pursuit of justice and healing for all Americans.